The clock is ticking on climate action in the oil and gas industry. As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has noted, accelerating the move away from fossil fuels is critical to protecting people and the planet from perilous climate disruption. To remain in the race to net zero, oil and gas companies must sprint ahead in the energy transition.

Unfortunately, as progress stalls on gas flaring reduction and windfall profits are allocated to shareholders instead of transition activities, the current state of oil and gas decarbonization looks more like a treadmill workout than a marathon. Publicly traded companies have begun to set climate targets, but to transform their businesses to meet these goals, have sold assets to operators that often lack comparable climate goals. With high-emitting facilities increasingly moving into the hands of less responsible operators, there’s no forward progress.

Oil and gas companies sell assets for a variety of reasons, whether to raise money for energy transition planning, move emissions off their books, or meet traditional objectives like repaying debt or increasing dividends. Regardless of the motivation, asset transfers can have significant climate consequences depending on the characteristics of buyers and sellers.

In a new report, “Transferred Emissions: How Risks in Oil and Gas M&A Could Hamper the Energy Transition,” we shine a light on the climate implications of oil and gas asset transfers.

Analyzing the last five years of upstream mergers and acquisitions, we found three important trends:

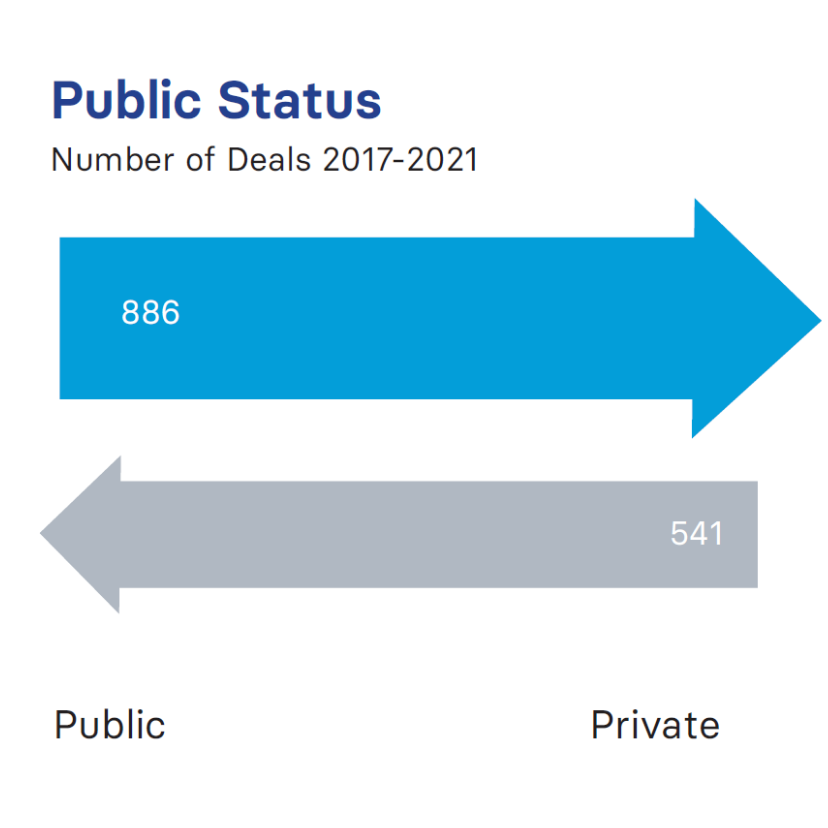

News outlets from the New York Times to The Economist have raised concerns about the drop-off in emissions reporting when oil and gas assets move from public to private markets. Though some private-equity-backed operators have taken strides to improve their climate disclosure in recent years, disclosure is typically more limited among private companies compared with their publicly traded peers.

Our research confirms that public-to-private transfers dominate the M&A landscape. In each of the last five years, public-to-private sales have comprised the largest share of annual deals. Over that entire period, public-to-private transactions have exceeded private-to-public deals by 64%. As a result, monitoring oil & gas GHG emissions could become significantly more difficult in the years ahead.

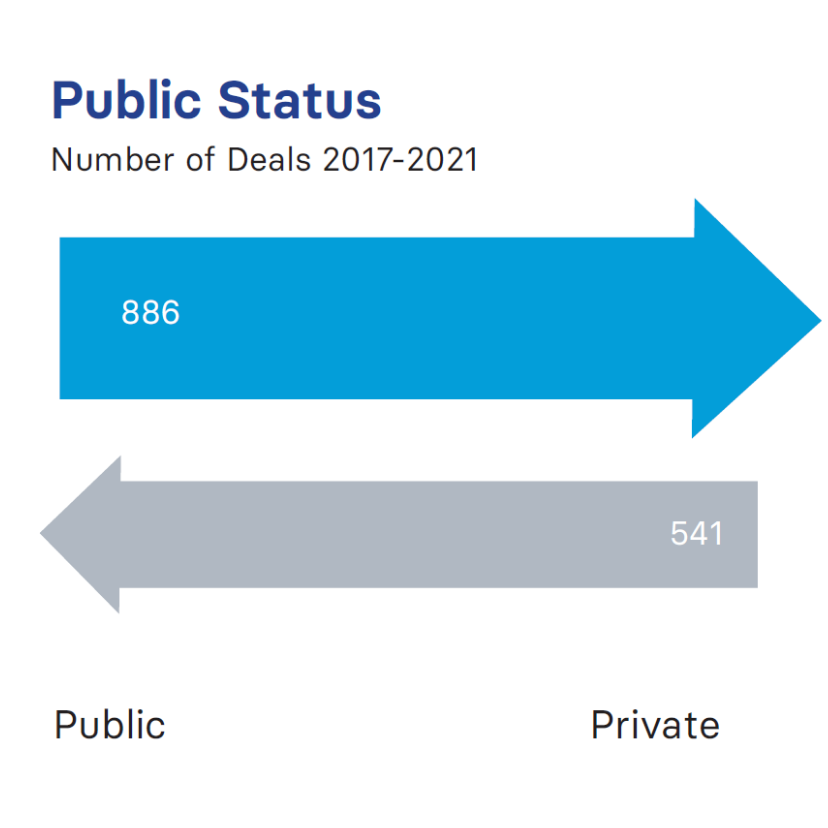

Oil and gas M&A not only jeopardizes climate disclosure, it threatens climate stewardship. Some of the companies that are most active in dealmaking are also industry leaders in the adoption of net zero goals, flaring reduction targets, and methane leak mitigation. Transferring assets to companies with weaker climate goals risks back-sliding on environmental performance.

Our analysis indicates that reduced-environmental-commitment deals are common and on the rise. Since 2017, billions of dollars of assets have moved away from companies that have set climate plans or participate in initiatives like the Oil and Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP) to improve methane management. These deals are becoming more frequent: while reduced-environmental-commitment deals comprised only 15% of annual transaction value in 2018, they now account for 30% of annual transfers.

Assuming that companies without methane, flaring, and net zero targets operate their facilities less responsibly than companies that have such standards, oil and gas M&A has setback emissions reduction for hundreds of assets.

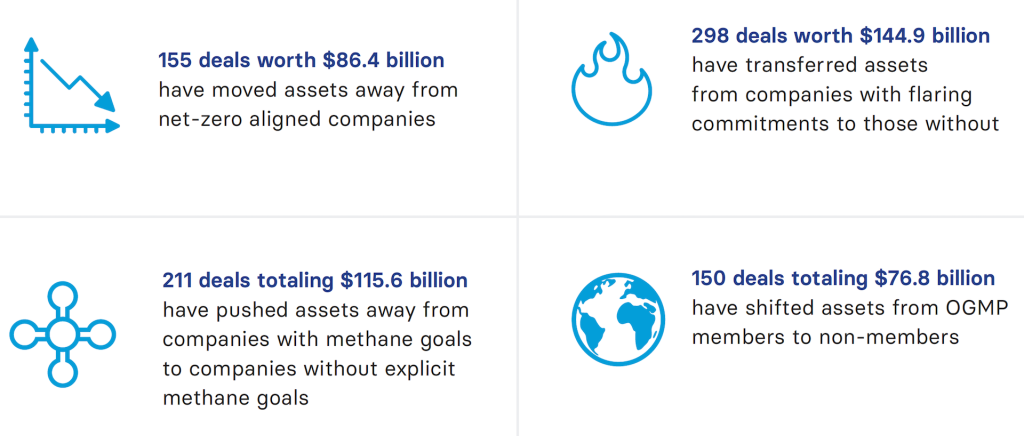

With oil and gas analytics firms ESG Dynamics and Capterio, we tracked shifts in climate stewardship at four upstream assets following changes in ownership. The results show that oil and gas M&A is increasing real-world emissions.

One example: in January 2021 Shell, TotalEnergies, and Eni – three majors with industry-leading climate standards – transferred the Umuechem oil field in the Niger Delta to Trans-Niger Oil and Gas, a private-equity-backed operator with no climate commitments. Following the transfer, flaring, a significant source of methane emissions, rose dramatically, with average weekly flaring more than quadrupling. The surge in post-deal flaring emissions illustrates how handing the keys to a less responsible operator can trigger significant climate consequences.

Energy M&A isn’t going away, but a new model of climate-aligned dealmaking is achievable.

Institutional investors can ask the companies they invest in to incorporate climate safeguards into M&A deal terms, while buyers can commit to enhanced climate disclosure, guarantee best-in-class methane mitigation and flaring reduction, and put up the funds for decommissioning. Companies selling assets can condition deals on commitment to these practices, while banks can ensure that climate standards are integrated in the transactions they facilitate.

Understanding the climate ramifications of upstream deal making is the first step towards solutions that sustain and enhance climate performance. Oil and gas companies, banks, and private equity are among some of the most sophisticated negotiators and deal makers in the world. By leveraging this expertise and working collaboratively to embed safeguards in upstream transactions, companies and their finance sector partners can pioneer a new model of M&A better suited for a net zero world.